MODULE III: Assimilation

Roles of Religious Leaders in Ministering to the

Afflicted and Affected1

Competency 4 - Understand that addiction erodes and blocks religious and spiritual development; and be able to effectively communicate the importance of spirituality and the practice of religion in recovery, using the scripture/sacred writings, traditions and rituals of the faith community.

Competency 5 - Be aware of the potential benefits of early intervention to the:

Addicted person

Family system

Affected children

Competency 6 - Be aware of appropriate pastoral interactions with the:

Addicted person

Family system

Affected children

Competency 7 - Be able to communicate and sustain:

An appropriate level of concern

Messages of hope and caring

The religious leader may adopt a multiplicity of roles to work effectively with a household adversely affected by addiction. These general role categories provide guidelines from which you may adapt, add or subtract, depending upon your religious tradition and understanding of ministry.

1. Catalyst constitutes one of the roles for leaders in ministry, since the religious leader is often the first line of assistance sought when there is a crisis. It is possible for the minister to serve as a catalyst in precipitating action to begin the process of alleviating the impact of alcoholism. If one is aware of the dynamics of the disease, (Modules I and II), then it is possible to inform people about the options and facilitate movement towards health and wholeness. The following factors need to be kept in mind as one seeks to be a catalyst.

- The denial factor is operative in those afflicted and affected by this illness. Never underestimate the power of denial! Alcoholism is metaphorically referred to as "the elephant in the living room" whose presence is not acknowledged. The power of denial is what keeps people shackled in the addictive system. It is extremely difficult to eradicate, even when the people involved realize that it detracts from their religious and spiritual development. Children will have been cautioned by other members of the household, or sense intuitively, NOT to speak about the situation and as a consequence, their religious and spiritual lives are impaired accordingly. Children also follow this "No Talk" rule because of the shame and stigma associated with alcoholism, as well as out of a sense of loyalty to the family. Counselors and religious leaders are encouraged to spend time with the children, listening to their stories, fears and concerns. NACoA has information available to help children of alcoholics (COAs). You can access information and tools at www.nacoa.org.

- Resistance is to be expected, particularly by the one who is addicted, but often by those who are affected as well. The reality of stigma and its concomitant feeling of disgrace shame, result in powerful resistance to change. One congregant quipped, "I can take being diagnosed with heart disease or even cancer, but please don't diagnose me as an alcoholic!" A laundry list of reasons will be given by all in the system as to why there are problems, except the fundamental reason, namely the presence of addiction. Expect that people will rationalize, minimize and trivialize the situation, both regarding the addicted person and the family members until uncontrollable chaos or a crisis occurs, which are evidence of denial and resistance. The quiet persistence on the part of the leader who can always link the problems and troubles to the disease is essential! This needs to be done in a patient, yet firm and persuasive manner. Many alcoholics know deep down in their gut, that they are addicted and, if the pain is great enough, may be waiting for someone to name the issue honestly. This will actually help spouses or partners and mature children understand that resisting change is tantamount to perpetuating the illness.

- Detach with love is the mantra that needs to be repeated to Oneself as a religious leader. As the religious leader, you are not responsible for the problem or for fixing the situation. Rather, you are consulted so as to be a part of the solution. In the course of working with a household, those adversely affected by the illness will have to learn this as well. It is critical to realize that detachment does not mean abandonment of the addicted person; rather it is unhooking emotionally from the addict, so as not to enable or become swept into the vortex of the illness. The illness can destroy those around the addict as well. The term used in conjunction with becoming enmeshed in the situation is codependency. For further elaboration on this concept, please see the discussion in the second section of this module. It is important to realize that children learn what they see and hear in this kind of a context. The life diminishing impact of the addiction can persist for generations unless the cycle is interrupted.

- Reality of risk is inherent in ministry at this point. Trusting relationships are a prerequisite for working and counseling with those who are addicted. Even when this is accomplished, there is always the risk of rejection when one names the illness and lovingly confronts those who are involved in its progression. For the sake of healing and health, risks need to be taken. Bear in mind that not to take risks is to enable the disease to continue. You may wish to use stories from your own religious tradition to illustrate how important it is to take risks for the sake of justice, liberation and health. Challenge the students to draw on their own religious heritage as a resource for examples of people who took risks for the sake of their faith tradition. Communicating the reality of risk to all of those involved in the addictive process is a difficult sales pitch. You may once again emphasize the paths that are available to the addict and her/his significant others by referring back to Module II, under the category of General Awareness Information.

- Telling the truth in love is possible if the religious leader has come to terms with her or his own attitude towards the illness and those suffering from it. The religious leader must be sufficiently self-differentiated to withstand the possible rejection that may ensue from honestly and lovingly naming the presence of the illness. A catalyst can say the following:

1. "I am not a diagnostician, but it feels like you are really hurting and I believe that addiction is at the root of your problems."

2. "I can hardly imagine the depth of the pain you are experiencing. I would say that addiction is a strong possibility and I can try to help you do something about that."

It is a fearful thing to "tell the truth in love" to another person. The moral imperative evident in religious and spiritual traditions makes this necessary in order that health and healing might occur.

2. Coordinator between those who are entangled in the addiction and linking them with resources that are available is another appropriate role.

- Information regarding resources is imperative for religious leaders to know in advance of encounters with the problem. One of the first things that religious leaders should secure for themselves are the names, phone numbers and web sites of community resources that deal with addiction when they first move into a community. This means information about detoxification centers, treatment centers, and where A.A., Al-Anon, Alateen, Adult Children of Alcoholics (ACOA) and other twelve step groups meet and their contact numbers. The fourth module will deal more in detail with these resources as a part of the action plan.

- Supplying pertinent materials for individuals, households, employers and others in the faith community is an important ministry. Pamphlets that enlighten and guide affected family members provide concrete assistance for people who are in desperate need. Remind students that such material can be placed in prominent positions in the synagogue, church, mosque or wherever a religious group may be meeting. Materials appropriate for children are also available and should be included.

- Cooperating with health care and other professionals in addressing addiction in the community is strongly recommended. Since alcoholism impacts all aspects of the alcoholic's health, cooperation with health care professionals is imperative. As is the case with knowing resources and pertinent material, the religious leader may need to take the initiative and get to know people who may be partners in ministry and who are in the medical profession, marriage and family counseling, law enforcement, legal assistance and social welfare. Forming an interdisciplinary team is most effective for dealing with a multidimensional illness. Cooperation rather than competition with other professionals in the community is imperative. For those who may be serving in rural or less populated areas of the country, additional efforts need to be expended in order to coordinate the nearest resources available.

- Be aware of the possibility of "intervention" as a way to interrupt the addictive process. An alcoholic does not necessarily have to "hit bottom" before s/he can be helped. Vernon Johnson writes about this in his book and calls it, "raising the bottom"2 so that the alcoholic and those affected by the addict will not have to lose everything before something can be done. Religious leaders should know how to contact people who are skilled in the intervention process. An outline of the basic tenets and the structure of an "intervention" are found in Module IV, Handout 1. (Note: Normally religious leaders are not equipped nor expected to conduct interventions. It is recommended that clergy understand intervention and know their community resources that can help facilitate one when needed, but generally clergy should remain in their appropriate role of support and not participate in an organized intervention. In some rare instances, the location of the faith community and the circumstances of the family may necessitate the religious leader participating in an intervention, but it is not generally recommended.)

3. Correlator of religious tradition and ministry to the addicted system is a critically important function of the religious leader.

- Knowledge of the posture of your religious tradition in relationship to addiction is imperative. What has your tradition historically said about addiction? Is it considered a sin or a sickness? Howard Clinebell has carefully delineated the various approaches that religious traditions have adopted.3 The attitude of your religious tradition as a whole shapes the attitude not only of the religious leader, but the entire community. If the attitude is negative, the difficulty and complexity of the problem is increased.

- Assisting with the theological interpretation of the illness is important to people in the faith community. As a minister, ask yourself how can my religious tradition be of help or support? What implications does the presence of this illness have for my own spiritual growth and development? What purpose or meaning is there in the experience of this illness? The "why" question, or the issue of theodicy comes to the fore. Other theological questions include:

- Is this Higher Power testing me and my loved ones?

- Is my Higher Power punishing me and my loved ones?

- Is this evidence of satanic or malevolent powers at work?

- Where is my Higher Power in my suffering?

- Is there any hope for our despair as we engage this disease?

- Is this Higher Power testing me and my loved ones?

- Addiction is only one of many crises that precipitate questions as they relate to the intersection of the realities of life and the tenets of faith. This module is NOT going to provide a format for the theological interpretation of addiction because the interpretation varies depending upon the faith tradition. These theological questions can provide grist for in-depth discussion among students who are engaged in theological study.

- Salient theological concerns that are inter-religious in nature are:

(Each of the following theological assertions could be processed in small groups if time permits.)

- Divine desire is for healing and health. All religious traditions seem to hold in common an understanding of the Divine as being desirous of healing and health for those who are suffering illnesses and pain. When the Higher Power in one's life, however that power is named, is imaged as benevolent and one that desires an abundant life for people, this Higher Power can be a powerful force for healing.

- Human beings have a proclivity for developing false gods in their lives. When the total energy of a person is expended in supporting an addictive habit, the substance itself begins to take the place of the Divine in that person's life.

- The reality of human imperfection is acknowledged in major religious traditions and needs to be appropriated. A book by Kurtz and Ketcham (2002) entitled, The Spirituality of Imperfection: Storytelling and the Search for Meaning, New York: Bantam Books, (reissue) provides a provocative text for those who are victimized by perfection as a defense against their sense of disgrace shame that could be prompted by their religious and spiritual interpretation of life.

- Religious communities have as a common goal to be hospitable to those who are marginalized in society. People suffering from addiction and often their family members have been marginalized by society and often by religious communities as well. You may wish to have students discuss how religious communities understand their purpose and mission in the world.

- All religious communities have rites, rituals, sacred texts and traditions that have a bearing on the way in which those suffering from addiction and those adversely affected by addiction can benefit from the ministry of the community. It is critically important to remind students that children are an important part of religious communities and addressing their unique situation needs to be included.

- The reality of hope is critical for people dealing with issues of addiction because the situation is often perceived as hopeless. The spirituality and religion that is most powerful in the recovery process is the one that holds out hope for all who are involved.

- Divine desire is for healing and health. All religious traditions seem to hold in common an understanding of the Divine as being desirous of healing and health for those who are suffering illnesses and pain. When the Higher Power in one's life, however that power is named, is imaged as benevolent and one that desires an abundant life for people, this Higher Power can be a powerful force for healing.

4. Confessor is one who hears the guilty plea of all who are involved in the addictive system.

- Formal rituals of confession are utilized by many religious traditions. When the religious leader is informed, there is an opportunity to talk about the broken relationships, hurtful behavior and pain that has been inflicted as a result of the illness. All significant others as well as the one addicted may have the need to share their feelings of animosity, disgust and hatred toward the disease of addiction, which is destroying their family. Challenge the students to think about ways in which confession is or is not a significant part of their spiritual discipline and religious thought.

- Counseling by the religious leader may constitute an informal time of confession. Deep seated resentments, painful memories of abuse and neglect often come to the fore as articulated by people caught in the web of addiction. An opportunity to process these issues with honesty and integrity becomes a form of confession. Naming the issues either formally or informally is a critical part of the ongoing process of healing from addiction. Gaining the trust of children and listening carefully without judgment to their stories, feelings, fears and concerns is a significant, but often overlooked or forgotten, dimension to ministry.

- Listening to the Fifth Step, while not considered as confession in the technical sense of the word as used in many religious traditions, it is a ministry that religious leaders can offer to all who are in need of sharing their inventory. See Fr. Mark Latcovich's article on the Fifth Step at www.nacoa.org in the Clergy section. (Further information about A.A. and the Twelve-Step Program will be addressed in the next module.)

5. Conciliator is the role a religious leader can assume in attempting to help restore broken relationships in the social system of those afflicted with and affected by addiction.

- Broken relationships dot the landscape of people in the addictive system. The religious leader can play a significant role in bringing about reconciliation. Sometimes the reconciliation process involves becoming reconciled to the fact that saving a relationship may not be possible. Children most often suffer the consequences of broken relationships and the abject fear of a system that crumbles. Press your students to put themselves in the place of a child who has no power, influence and voice in their destiny. This should heighten the awareness of the spiritual damage that can be inflicted when reconciliation, however defined, does not occur.

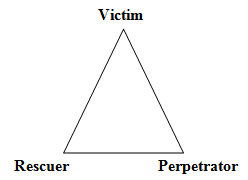

- Identifying the role played by each person in the addictive system not in order to assign blame, but to assist in realizing how the illness manifests itself in relationships. The following diagram indicates one way in which roles are played in the addictive household.

The victim is the person who appears to be blamed for everything amiss in the system. The perpetrator is seen as the one who perpetuates the blaming process. The rescuer attempts to save the victim from the perpetrator and becomes even more enmeshed in the dysfunctional system. The roles assumed or assigned to children were covered in Module II. It may be helpful to review those roles and to see how they fit into the pattern of the household impacted by addiction.

- A willingness to forgive is essential in the healing process. Religious leaders need to be prepared for the fact that there will be some people who are unwilling to forgive the addict or perhaps find it impossible to be in the presence of the addict. Forgiveness is tantamount to any possibility for a restorative relationship to develop. Children are often more willing to forgive than are adults!

- A desire to be forgiven is critical to the process of reconciliation. Each situation will present its own unique challenges, whether it is finding reconciliation with other members of the household, with neighbors, friends or co-workers, those in the addictive system often have a need to clear the slate as it were. Children are often most sensitive to the attitudes and dispositions of those around them. They should be encouraged to share their feelings and fears as they encounter the disruptions in the household.

There are hazards in ministry as one seeks to be a part of the solution rather than become a part of the problem. This is why it is so essential that students become aware of their own history, attitudes and responses to the phenomenon of addiction. As indicated in the section entitled Catalyst, an understanding of codependency is important for the religious leader as well as members of the household who become trapped in roles and relationships that often exacerbate rather than attenuate the addiction issue.

1. These categories are taken from, Robert H. Albers, The Theological and Psychological Dynamics of Transformation in the Recovery from the Disease of Alcoholism. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1982. 369-386.

2. Vernon Johnson, I'll Quit Tomorrow. New York: Harper and Row, 1980.

3. Howard Clinebell. Ministering to the Alcoholic, Drug Addicts and Other Behavioral Addictions. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1998, 287-300.

Module Home • Introduction • Roles of Religious Leaders in Ministering to the Afflicted and Affected • Codependency • Class Activity • Case Study